Why emotional storytelling is the future of journalism

I gave the following keynote on the media stage at the Fifteen Seconds Festival, an interdisciplinary festival for business, innovation, and creativity, in Graz, Austria on June 6, 2019.

I’ve never confessed this in front of such a large audience before, but, I’m a nerd. And if there’s one thing that I’ve always been passionate about, it’s computer games.

Growing in Hong Kong as a kid in the 80s, in between getting straight As at school, and then piano lessons and swimming lessons and judo lessons, computer games were my escape. I still remember my sense of anticipation at being able to escape into and explore a mysterious new world the first time I popped the Myst CD into my computer’s CD-ROM drive. Or my plaintive cries of “Just one more turn, mom!” when I was deep into a game of civilisation and it was past my bedtime.

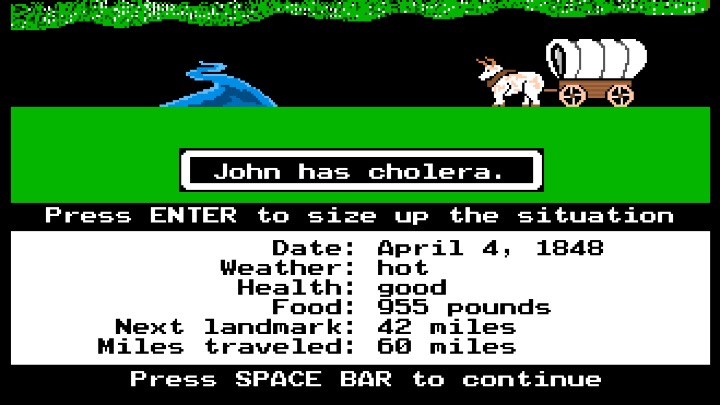

Or, indeed, my sense of frustration when playing Oregon Trail, and half of my settlers would die of horrific diseases before we made it even half-way across.

But it wasn’t all just fun and games for me. I learnt a lot by playing computer games while growing up. Granted, some lessons were more useful than others: When I finally got into Yale and moved to live in America for the first time, I was a little bit surprised that not everyone was setting off in covered wagons to go conquer the West.

But other lessons stood me in good stead. I learnt teamwork, and strategy, and friendly competition. The biggest lesson, though was this: There is something magical that happens when you can combine stories with systems.

So take Oregon Trail for example. The stories were the ones that I told myself about my plucky band of explorers, and the trials and tribulations they went through as they headed west. The system was the map of the US. The weather. How far the settlers could actually go in a day. And the system taught me the value of calculated risk-taking, and careful management of resources.

Fast forward 10 years, and I’m working in London for the Financial Times. I’m still a nerd, but now I’m a news nerd, which means both that I was using code and programming to do journalism, and also that I’m asking questions about the story and the systems of journalism: What is the mission of what we do? What systems - workflows, networks, organisations - enable us to do this work? And, crucially, how can we do it better?

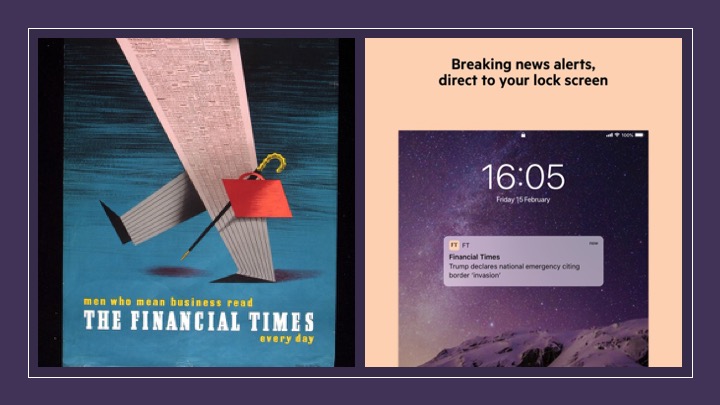

It was a good time to be thinking these deep, weighty questions about the future of journalism, because the industry as a whole, and the Financial Times was no exception, was undergoing massive change and disruption. Readers were shifting from the newspaper to digital devices. When I first joined the Financial Times 12 years ago, 80%, or four out of every five subscriber were print-only. They were literally buying a newspaper from us. Today, the same proportion - 80% - are digital-only subscribers. We have subscribers who have never seen the FT in print before and wonder about why our website has this strange pink-coloured background.

And one question that I kept returning to, was that despite all this change and disruption, the news reading experience remained mostly the same as it was when I was growing up.

Audience engagement was starting to become a big deal in many newsrooms including ours, but it was mostly concerned with questions of before and after. So for example, before you, as a reader, arrive at an FT article, how can we use search engine optimisation to help you find the relevant article more easily? Or, after you’ve finished reading an article, how can we encourage you to comment below the line or to share the article on social media?

So, being a good millennial, I decided to follow my passion. I wondered what would happen if we could combine the magic and power of video games, with the rigour and reporting of journalism? What if we could make a really good news game?

And so we did.

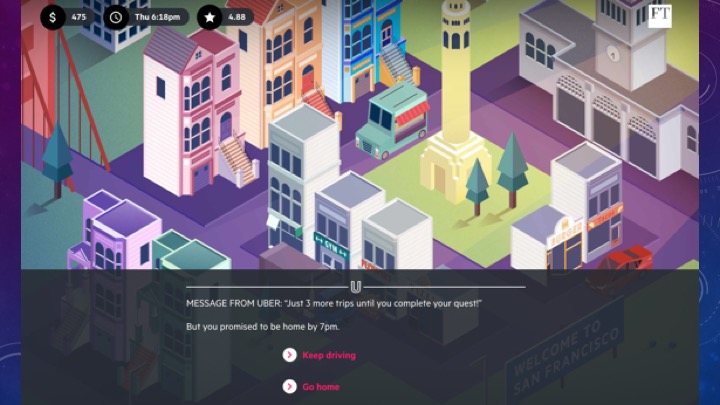

We made The Uber Game. It’s available for free at ft.com/ubergame. In this game, you play as a full-time Uber driver in San Francisco, trying to make a living.

You have a week to make a thousand dollars, and you do so by driving around the city and completing rides. And in the course of doing so, you come across different dilemma.

For example, in this one, you had promised your son to be home by 7pm to help him with his homework. It’s getting close to that time, but you get a message from Uber that says you have just a few more rides before you complete your quest, which earns you a big cash bonus. Do you keep driving, or do you keep your promise?

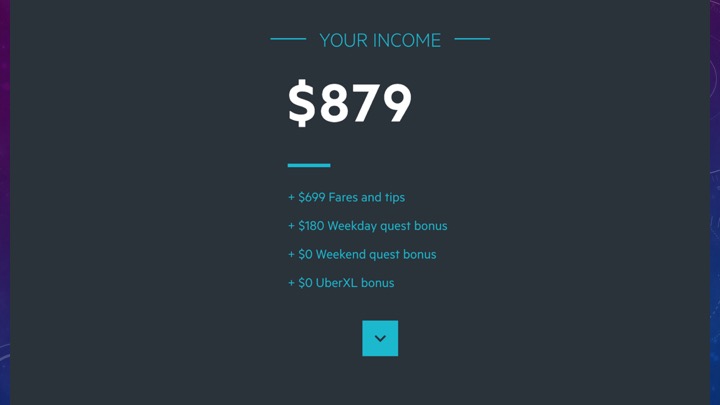

Everything in the Uber Game is journalism and comes from reported facts. We interviewed dozens of Uber drivers to source not just the stories - the scenarios and dilemmas that you come across in the game - but also the numbers that underpin the system. We asked very specific questions, like, how many rides do you complete on average in an hour? or how much do you actually earn if you complete a quest?

And on the flip side, the costs - the parts that are often overlooked. What is your fuel cost per month? or how much do you have to budget for repairs?

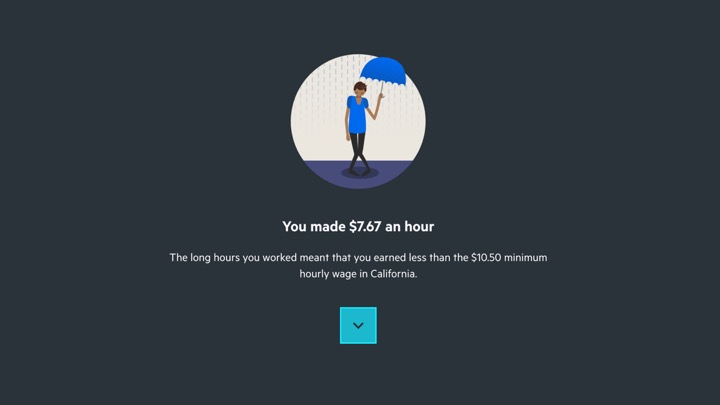

And what the game teaches you, is that when you combine your revenue and your costs, your profits are often less than you expect them to be.

The Uber Game was a big success for us. Nearly half a million people have now played the game, and they have each spent 20 minutes, on average, playing the game. To put this into context, our average time on page for an FT article is just over a minute.

We talk a lot about the attention economy these days. About how people’s attention spans are getting shorter and how there are more digital distractions. In response, the journalism industry has largely tried to figure out ways to fit what we do around people’s busy schedules: how do we make content more bite-sized and snackable, or how can we get our newsletter into your inbox early in the morning before you start your day.

But if we are to fulfil our mission as journalists, which is to help people understand and navigate the world, and to make better decisions, then we are inevitably going to have to tell more complex and nuanced stories. And so while it’s noble and important to make consuming the news more efficient, maybe we are sometimes going about this the entirely wrong way around. Maybe instead of fitting our journalism around people’s increasingly busy schedules, we should be asking ourselves how we can create compelling and engaging enough experiences that people will make time for.

Oh, and yeah. We won a bunch of awards for the Uber Game, in both journalism and innovation awards, so that was cool.

I’d love to stand here and tell this beautiful story about how this childhood passion of mine enabled us to create a successful newsgame, but the reality is that I’m by no means a trained, professional game designer. So when we set out to make the Uber Game, I knew I needed help.

Fortunately, I made a personal resolution several years ago, which was to be more interdisciplinary in my approach to conference-going (which, in part, explains my presence here today). Instead of going to journalism conferences every year and meeting the same people, I decided to go to other people’s conferences, in adjacent industries. And given my passions, the very first one that I went to was a game designer’s conference.

It was there that I met Celia Hodent. Many you won’t know who Celia Hodent is, but you probably recognise her work. How many of you have heard of Fortnite?

Celia, who worked for Epic Games at the time, helped design the tutorial. Through her work, she taught 250 million people how to navigate and make decisions in that complex game-world.

One of the points that Celia makes, is that emotions affect cognition. You learn better when you’re not just given a set of facts about what happens in the game, but when Fortnite engages your emotions.

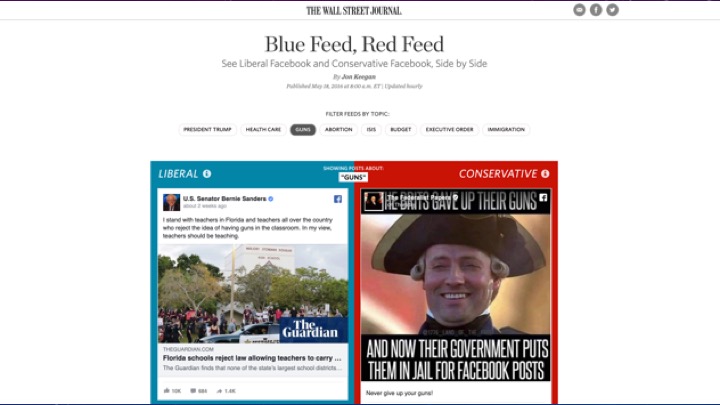

So, emotional storytelling is powerful. It can help shape people’s worldviews, and through doing so, affect their cognition. And we know this works, because we’ve seen it in action in journalism.

We’ve seen it in action in tabloid newspapers that prey on people’s fear and anxiety and sense of scarcity. We’ve seen it in action in talk shows that rile up people’s anger and sense of injustice.

And more recently, we’ve seen it in action in social media, where the power of targetted advertising has led to the creation of memes and posts that are specifically designed to manipulate people through their emotions. This was, in essence, the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

All of this is creating a world that is more fragmented, more divided, and more tribal than ever before. It is creating a crisis for journalism, because people don’t trust us, the journalists, and the work that we do anymore. They are more likely to shout “fake news!” when they come across something they don’t like, rather than engage with the facts in healthy debate.

But… maybe it doesn’t have to be that way. Maybe we can use the power of emotional storytelling for good.

Maybe we can use it to spark people’s curiosity, and help make their world bigger instead of smaller.

And maybe, in a world that is fragmented and tribal, we as journalists have a duty to do more than just report the facts and rationally analyse the arguments and to help convey emotional understanding. Maybe we need journalism that provides empathy-as-a-service.

And so we tried to do just that.

Before I move on to this next example, let me check in with y’all, and ask: “What comes into your mind when I say the words The Irish Backstop?”

So, probably something Brexit-related. Probably something about politicians bickering and disagreeing with each other. Probably something technical about customs arrangements at the Irish border.

In short, probably something quite abstract. But of course the Irish border is a real place with real people living on both sides of it, and to them, what happens at the border in the event of a no-deal Brexit is not abstract at all, but a real, and very emotionally charged issue.

We tried to convey this depth of feeling, and this sense of emotional understanding, to our audience - and now to you - through this:

This video was filmed, directed and masterminded by my colleague Juliet Riddell. We commissioned Clare Dwyer Hogg, an Irish poet, to write an original poem about Brexit and the Irish backstop, based off of articles that we have written in the FT. We asked the Irish actor Stephen Rea to perform a reading of it on location at the actual border, which Juliet turned into this beautiful film.

So, to recap: We’ve turned to game designers for help to make the news experience more interactive and more engaging. We’ve collaborated with poets to help us convey emotional understanding. The next question we asked ourselves, was: what if the news experience was embodied, and much more of a two-way conversation between audience and storyteller?

For this, we turned to theatre-makers and artists for help.

In the summer of last year, we did a small experiment with the Battersea Arts Centre and Queen Mary University. We paired five FT journalists up with artists and theatre makers. The question we posed to our journalists was this: What is it in your beat, and what you cover, that you find really important but hard to convey to our audience through just writing traditional articles in the FT? The artists then took the answer as their prompt, and they had just a week to try to come up with something that responded to that challenge.

One of the pieces was this game called Ten that is about climate change. It came about because Leslie Hook, our climate reporter, said that one of the hard things is that the important parts of climate change are all about systems - systemic issues, the dynamic in systems when, for example, countries got together for the Paris Climate Talks. But it is hard to make these systemic issues engaging because people are fundamentally drawn to stories. They want to hear about the town that will be submerged when sea level rises.

So Tassos, the artist, took that and created this game, where everyone in the room had a card, some with secret instructions on it. You and to discuss and negotiate with each other, and the game mimicked the tension between personal self-interest and collective responsibility that exists in, for example, the climate change talks.

Other pieces that came out of that were:

- We turned a set of interview transcripts and notes into a rap and spoken word performance

- We had a piece of conceptual artwork that compared blockchain to human memory

- We had a piece of participatory theatre that explored grief and technology

- We brought our Work Tribes column to life with a series of live performance vignettes

The experiment at the Battersea Arts Centre was just that - an experiment. It was a small first step towards figuring out how artists and journalists could collaborate effectively. But what it led to was the discovery that we weren’t alone, and that there were lots of people in both theatre and journalism who are interested in exploring this in-between space.

So at the end of last year I flew down to Johannesburg, in South Africa, for a project funded by the Open Societies Foundation. It was structured very similarly to what we did at the Battersea Arts Centre: It paired up investigative journalists with local artists to create new works that reached audiences who would not normally either buy a newspaper, or buy a ticket to go into a theatre.

This is the De Balie culture centre in Amsterdam, where for the last few months they have been conducting a very interesting experiment in live journalism, and asking the question of what it means to bring an investigation and reporting into a topic into a space over a period of several months.

They are using theatre and performance to not just convey an emotional understanding, but also to create a space for dialogue between people on different sides of an issue. In this project, the facts are the jumping-off point to explore both the stories and the system.

I’m proud to be a nerd, and a news nerd, because it gives me optimism and enthusiasm about how journalism can grow and thrive at a time when there is a lot of doom and gloom about our industry. So, to close, I’d like to tell you about some of the future possibilities and interdisciplinary spaces that I’m excited to explore next.

As more news organisations become subscription- and membership-based, what can we learn from sports teams and churches about growing and nurturing a following?

What can we learn from Instagram influencers, and fashion designers, about how our work helps shape people’s sense of self image, self identity and self worth?

As we design our news apps and news sites, what can we learn from museum curators about how to create spaces for serendipity, learning and delight?

What to read next: What art and drama can do for journalism